Equational Programming

Table of Contents

Strategies

strategy: how to reduce a term

normalising strategy: gives a reduction sequence to a normal form. leftmost outermost.

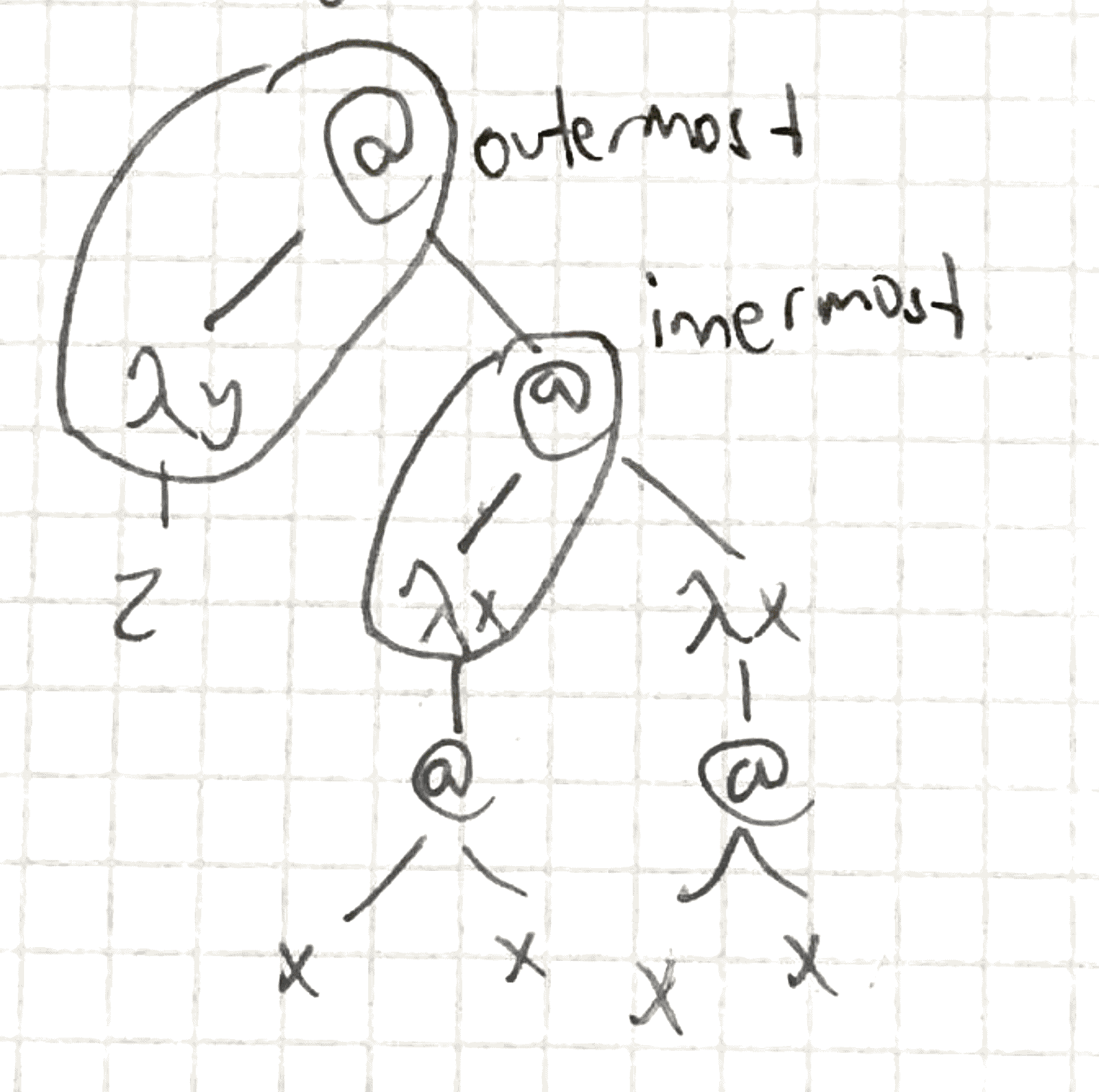

e.g. given: (λy.z)(Ω)

- Outermost: not contained in another redex

- Innermost: does not contain another redex

- Leftmost: the one most on the left obviously

Call by need

reduce in every step the leftmost outermost redex. if it finds a loop, no normal form.

e.g. in above: (λy.z)(Ω) ➝ β z

another e.g.: (λx.fxx)((λx.x) 3) ➝ β f ((λx.x) 3) ((λx.x) 3) ➝ β f 3 3

pros:

- normalising

- all steps contribute to normal form cons:

- redexes may be copied

- difficult to implement

Call by value

Reduce in every step the leftmost innermost redex.

e.g. in above: (λy.z)(Ω) ➝ β (λ.z)(Ω) ➝ β (λy.z)(Ω) ➝ β …

e.g.: (λx.fxx) ((λx.x)3) ➝ β (λx.fxx) 3 ➝ β f 3 3

pros:

- redexes not copied

- easy to implement cons:

- not normalising

- reduction to normal form may reduce redexes that don’t contribute to normal form

Rightmost-outermost: not normalizing!

Rightmost outermost is not normalising. For example, take the term ((λx.x)(λx.y))(Ω).

Leftmost outermost:

((λx.x)(λx.y))(Ω) => (λx.y)(Ω) [reduces the λx.x]

=> y

Rightmost outermost:

((λx.x)(λx.y))(Ω) => ((λx.x)(λx.y))(Ω)

= ((λx.x)(λx.y))((λx.xx)(λx.xx)) [reduces the application in Ω]

=> ((λx.x)(λx.y))(Ω)

=> ((λx.x)(λx.y))(Ω)

=> etc.

It’s easier to see this if you draw the tree. An application with an application on the left side can’t be a redex. The leftmost outermost redex is the λx.x, whereas the rightmost outermost strategy reduces the application inside the Ω.

Leftmost outermost gives a result, while rightmost outermost goes into a loop. Therefore, rightmost outermost is not a normalizing strategy.